The use of marijuana has been prohibited for quite some time in the United States. From the early 1940’s onward, marijuana users have been mainly viewed as criminals. This perception has shifted over time, but is directly tied to America’s history with narcotics. After the Federal Bureau of Narcotics was formed in 1930, drug prohibition expanded in the United States. However, in the late 1990s, California and other states legalized the use of marijuana for medicinal purposes. Little by little, certain other states did the same, and some eventually legalized it for recreational use. Today, about half of U.S. states, plus the District of Columbia, tolerate some form of legalized marijuana use. Regardless of these developments, marijuana is still a controversial issue, especially regarding its efficacy for medical use, its effect on individuals, and on society. The media have played a prominent role in the debate, and the have been instrumental in influencing people’s perspectives.

According to the 1998 PBS Frontline documentary “Busted: America’s War on Marijuana,” marijuana was grown in the U.S. colonies for hemp fiber as early as 1619, was later used for medicinal purposes and was popularized for recreational use after the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), when large numbers of Mexicans immigrated to the United States. Under the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, distributors and producers of narcotics were required to register with the IRS, record their sales data, and pay a federal tax. As resentment and fear of Mexican immigrants grew, this act was the starting point in which marijuana use was related to crimes and users were regarded as immoral. In 1915, for the first time, marijuana use was prohibited in California and, during the 1930s, marijuana use emerged as a serious concern for the U.S. government.

In her essay “Getting Framed: The Media Shape Reality,” Charlotte Ryan states: “Framing is more than a process of interpreting selected events; it is actually the process of creating events, of signifying, from the vast pool of daily occurrences, what is important” (Ryan 1991:53). Media helps shape the public’s collective understanding of issues and, by highlighting fears about drug use, U.S. government media campaigns have been influential in prohibiting the use of marijuana. As the mass media related the use of drugs to crime and violence, the nation began to be fearful of people linked to marijuana and harbored antipathy toward its use.

In the early 1900’s, U.S. news framing of marijuana targeted Mexican immigrants by relating marijuana use to violent crimes. According to Marijuana, Mexico and The Media by C.W. Trujillo, “the drug was considered particularly dangerous because of its alien Mexican origins” (13). News stories that related marijuana use with criminal activity among Mexicans were intended to make the public panic by defining marijuana as a risky drug that caused violent crimes. Such news frames were reinforced in early Hollywood westerns that were full of images of “dangerous” and “immoral” Mexican “banditos.”

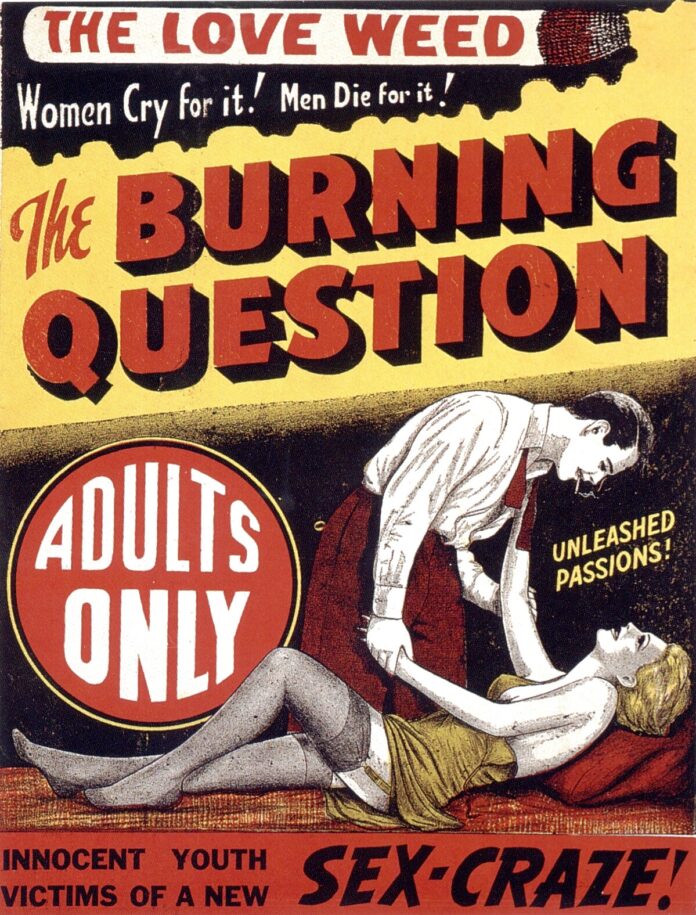

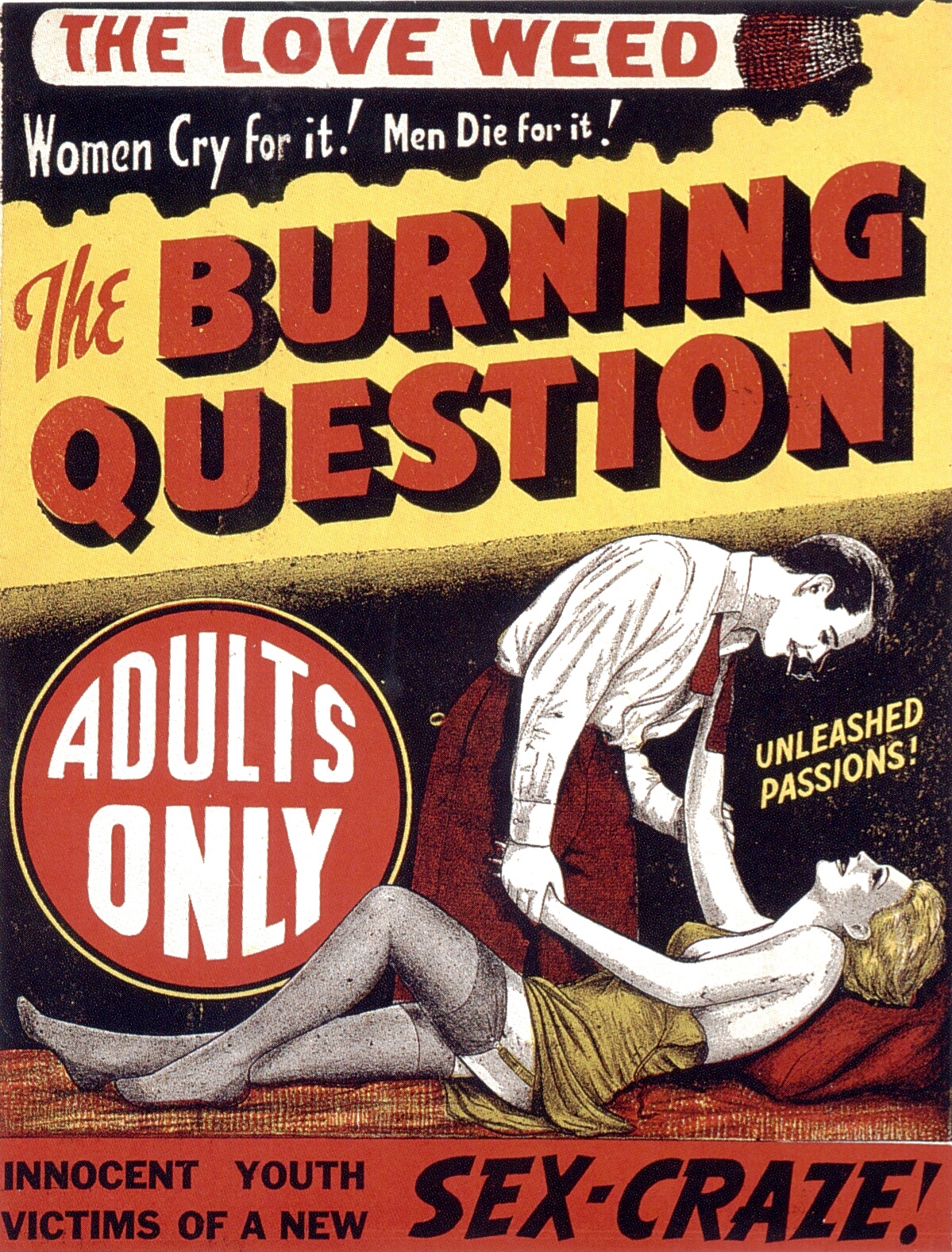

With widespread unemployment and poverty in the US during the Great Depression (1929-1939), there were many national anti-marijuana propaganda campaigns from the 1930s onward. Newspapers and magazines portrayed marijuana as a “killer weed, the weed of madness, a sex-crazed drug menace, the burning weed of hell, and a gloomy monster of destruction” (Orsini 2015:8). Marijuana users were framed as becoming instantly addicted, sexually promiscuous, violent criminals. The head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN), Harry J. Anslinger, was a prominent figure active in marijuana prohibition during the 1930’s. Under Anslinger, the FBN strengthened the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, further criminalizing marijuana use, by using racist stereotypes of Mexicans. Trujillo quotes a letter from Anslinger published in the Alamosa Daily Courier:

“I wish I could show you what a small [marijuana] cigarette can do to one of our degenerate Spanish-speaking residents. That’s why our problem is so great; the greatest percentage of our population is composed of Spanish-speaking persons, most of who are low mentally, because of social and racial conditions,” (Trujillo: 2011, 103).

In addition, Anslinger supported a now famous anti-marijuana propaganda film called Reefer Madness, in which young people were depicted as ruining their lives by smoking marijuana. This film warned the U.S. public, especially parents, about the dangers of marijuana to teens and children. Finally, in 1937, Anslinger accomplished his goal of criminalizing marijuana, by imposing a prohibitive tax on its import.

Attitude Adjustment

During the 1970’s, President Richard Nixon publicly defined drug addiction as an “infectious disease which was spreading to suburbia” (Orsini, 19), using phrases such as “plague” and “epidemic” when discussing marijuana (Trujillo, 16). As the president officially declared a War on Drugs, the media used a “problem frame,” which means “a narrative structure based on danger and fear” (Orsini 2015:14). This frame, which opposed recreational or medicinal use of marijuana, assisted in developing anti-drug movements like the “Just Say No” campaign started by Nancy Reagan, wife of President Ronald Reagan. This campaign spurred other campaigns with similar agendas by parents concerned about their children getting addicted to marijuana. In Atlanta, Georgia in 1976, one family began an anti-marijuana “Parents’ Movement” which spread via the news media, and became a huge grassroots-activism campaign that lasted for four years, branching out to England, Finland, Mexico, Jamaica and other countries (Dufton 2016, 213).

However, U.S. attitudes toward marijuana gradually shifted over time, as people came to realize that most users were not violent and that, in fact, increasing numbers of medical studies showed positive effects of marijuana use for a variety of health conditions. In what was a historic year, California legalized medicinal marijuana in 1996. Prop 215, known as The Compassionate Care Act, legalized medical use of marijuana for patients suffering from chronic illnesses like AIDS, glaucoma, and arthritis. During this momentous occasion, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) maintained their strict stance that marijuana had no accepted medical use, with the DEA listing marijuana as a Schedule 1 substance, along with heroin, LSD, and Ecstasy. Schedule 1 drugs are defined as “drugs that have no accepted medical use, and have a high potential for abuse.” In contrast, cocaine and prescription pills like Oxycontin, Adderall, and Ritalin are listed as Schedule II drugs, which are considered less dangerous.

Media framing of marijuana’s medical benefits increased significantly in the late 1990s and 2000s. The New England Journal of Medicine editorial board endorsed medical marijuana in 1997, noting that it was less dangerous than other drugs used on patients, stating: “Federal policy is hypocritical since doctors are allowed to prescribe morphine and meperidine.” They argued that excessive doses of such drugs could “hasten death,” while “there is no risk of death from smoking marijuana” (Kassirer, 1997). In the report Marijuana as Medicine, published in 2000 by the National Academy Press (comprised of members of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine), marijuana was discussed as having positive benefits for seriously ill patients, but was also said to have serious negative health effects like causing cancer: “Since marijuana users generally inhale more deeply than tobacco smokers, they may be exposing their lungs to even higher levels of these dangerous substances” (Mack and Joy: 2000, 41).

Opponents of medicinal marijuana use argued that the health benefits were dubious, that it was a “gateway drug,” and that it gave impressionable children the false sense that it was safe or acceptable to smoke. Former U.S. presidents Ford, Carter, and Bush released a statement urging voters to reject state medical marijuana ballot initiatives. Despite their pleading, medical marijuana laws were passed in 1998 in Alaska, Washington, and Oregon. The DEA expressed its concern that the medical marijuana movement was a stepping stone to legalizing recreational marijuana use. In 2001, President George W. Bush’s White House spokesman, Ari Fleischer, stated in a press briefing that Bush opposed its legalization (NBC 2001). This became a prominent discussion in the news, where the issue was framed as a states rights -vs- federal issue. In fact, in the 2000s, 33 percent of all news editorials focused on the legal framing of marijuana by states vs. the federal government (Golan, 2010, 50).

In the early 2000s, more states legalized medicinal marijuana, with the assistance of organizations like the Marijuana Policy Project (MPP). MPP paid for advertisements on 100 radio stations displaying prominent figures who had smoked pot in their youth, including President George W. Bush, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, and Vice President Al Gore. The radio ad asked: “Is it fair to arrest three quarters of a million people a year for doing what presidents and a Supreme Court justice have done?” Moving the frame of marijuana to political leaders who had smoked pot in their youth without suffering negative impacts was helpful in the evolution of U.S. public opinion.

In recent years, marijuana’s framing on television shows has also become more friendly. In an interview with The Atlantic, Director of Communications and Public Education for the Parents Television Council Melissa Henson argued that TV shows with marijuana use “communicate the idea that it’s not only acceptable behavior, but normal behavior. There’s a wink and a nudge when it comes to pot use on television” (Henson, 2012). Popular television shows like The Simpsons, Family Guy, and South Park ran entire episodes about the legalization of marijuana (Meslow 2012).

Yet, even in the mid 2010s, news framing of marijuana was still largely negative. When Trayvon Martin was killed in Florida in 2012, for example, a common news frame noted that there was marijuana in Martin’s bloodstream and whether or not this could have caused his death. On the Nancy Grace TV show on the HLN network, a segment on Martin was called: “Does Pot Make you Violent?” (Nancy Grace Show Jan. 18, 2014). Also framing marijuana in a negative light, then-FOX News Host Bill O’Reilly stated in The O’Reilly Factor: “The legalization of marijuana, still full of unintended consequences, sends a signal to children that drug use is an acceptable part of life” (O’Reilly 2014). Likewise, in a February 6, 2009 story, “Phelps Accepts ‘fair’ Punishment,” BBC News showed a photo of U.S. Olympic swimmer Michael Phelps smoking marijuana, and noted that Phelps had publicly apologized for his “regrettable” behavior and “bad judgment.” Using a “shaming” frame, the article noted that Phelps also was punished for his marijuana use, with a three-month ban from swimming competitions.

Despite more states legalizing the recreational use of marijuana, including Massachusetts, Nevada, California and Maine in the November 2016 election, the DEA’s hardline position has remained the same. In 2014, though, Obama declared that marijuana use is not “more dangerous than alcohol” (Peralta Jan 2014, 1). This was the furthest any U.S. president had ever gone in expressing support for marijuana. And, in the 2016 presidential election, Bernie Sanders spoke openly as a proponent of legalizing marijuana. U.S. attitudes on this topic have drastically changed over time, with media framing affecting how we view the issue. In the 1990s, 81 percent of Americans were against marijuana legalization, but now, 53 percent support legalization (Geiger Oct. 2016: 1). Times sure have changed!