“Booktubing” craze attracts GenZ’ers eager for personality-driven video connection

Four years ago on a hot day during finals, Rutgers University student Justin Staley hopped out of his dorm bed, to check out the only thing he was looking forward to that morning: a book review.

“Negroland: A Memoir,” by Margo Jefferson, had just been released, and Staley was excited to see the first critiques published in well-known newspaper. He’d been fascinated with nonfiction since he’d been a teenager.

Four years later, he woke up with the same sense of excitement, but for a slightly different reason: he’d shifted his review consumption from paper to screen. He’s now joined the growing global practice of “booktubing.” Staley has his own nonfiction booktubing channel on YouTube called “Ghostreader”, which has attracted nearly 2,000 subscribers.

Hearing is the new reading

Booktubing is driven by a group of content creators who, through vlog-style video, film themselves discussing and reviewing books. All booktube channels are on YouTube, and each booktuber covers the genres of his or her choice.

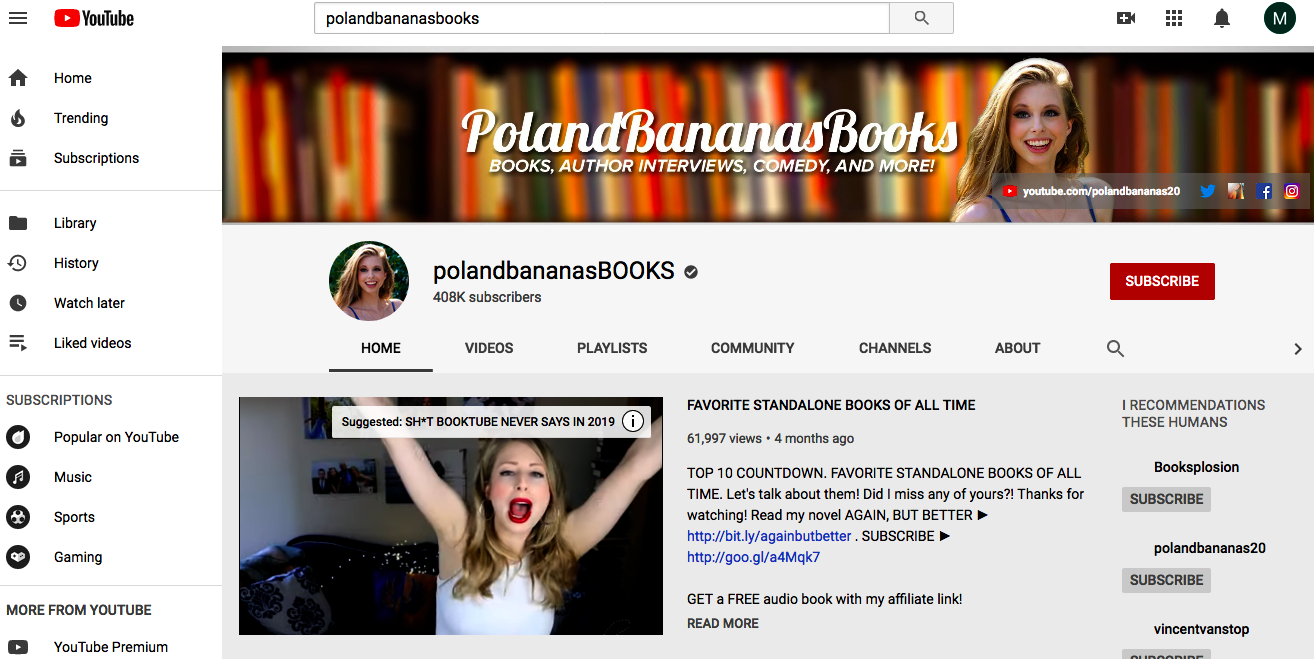

Booktube’s popularity has skyrocketed in recent years, with its most popular channel “PolandBananasBooks” developed by New Jersey native Christine Riccio. “PolandBananasBooks” has attracted more than 400,000 subscribers — and Riccio has since branched out, and written a novel of her own.

Booktubing has also captured the attention of celebrities, including former first lady Michelle Obama.

Though Staley loved traditional print reviews, he felt they’d lacked something. He believes the disconnect between readers and traditional reviews helps drive booktubing’s popularity.

“It makes it a lot more available to people, instead of just reading newspaper book reviews, and which [are] terrible, because [they’re] filtered by an editor,” Staley said. “Booktube has made more people not comfortable with a news writing format; [they have] the opportunity to now judge books as well.”

Since he was kid, reading was Staley’s escape from the violence happening around him. After graduating from university, instead of putting his engineering degree to work, he chose to become a successful booktuber. He says he has no regrets.

“Every time I post a video, all the other booktubers would text me, extending their support,” he said. “My dream on this channel is to continue on growing my viewers, and educating them further.”

Staley makes money from his channel, by running ads. The more subscribers booktubers attract, the more money they make from advertising.

“I don’t want to say how much money I make exactly, but I make a lot more than what I did before, when I was an engineer — believe or not,” Staley said.

Advertisers pay booktubers based each video’s number of subscribers, and views. According to Staley, some booktubers make as much as 75 cents per ad view. So hypothetically, if Staley attracted at least 1,000 views for a vlog, he’d make $750. Ad sponsors are mostly non-book related, and include companies such as Apple, Budweiser and Warner Brothers. Spokespeople contacted from these companies did not respond to requests for comment.

“I get to work from home too, so I’m chilling,” Staley added.

How booktubing took off

Riccio had always enjoyed making silly YouTube videos with her younger sister. She also liked reading books, though she never discussed them with anyone else. When “The Hunger Games,” a novel and subsequent series by Suzanne Collins, came out in 2010, Ricco was among the thousands of people lined up outside bookstores to get a copy.

She decided to combine her interests, by broadcasting her reactions to the book on YouTube. She’s credited as the first to do so.

“Why not? I think a lot of people during that time used YouTube as a way to do something we’re not particularly comfortable with,” Ricco recalled. “I was shy, no question about it — a terrible public speaker. Couldn’t even talk to my friends without avoiding eye contact. But talking to a camera with no one physically judging you allowed me to talk about something that I have enjoyed — and that was reading.”

Riccio was a college student by. By the end of 2010, her channel had 1,000 subscribers; by the following year, 5,000; and by 2019 she commanded the largest booktube channel, with 400,000 subscribers.

“Never expected it to get this big, to be honest,” she said. “You need to realize that everything was new. YouTube was new, this whole concept of talking about books through video was new.”

Riccio inspired others. Now there about 130 known booktube channels.

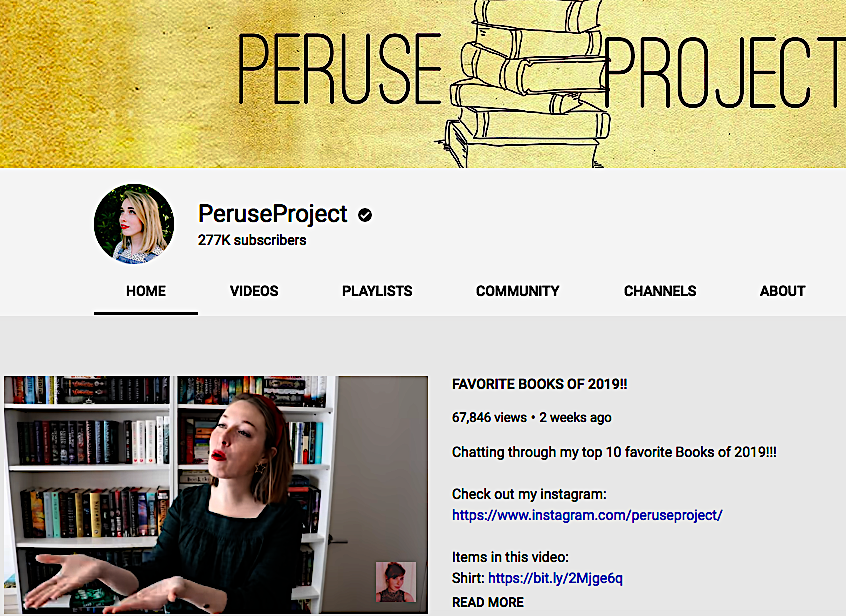

Regan Perusse is the director of “booktubing fam” organizing, meaning that she makes sure that any event promoting online video vlogs includes booktubers. She says many people modeled their channels on Riccio’s, and that she’s grateful that Ricco opened the door them.

“She gave us all a voice, to talk about our books through our personalities, which is what makes this field so unique,” said Perusse, a New York-area program analyst who runs the 277,000-subscriber “PeruseProject “as a sideline.

Sarah Earlington, a student at New Jersey’s Seton Hall University, says she had no interest in reading books until she came across booktuber Scott Thomas’ “Book Invasion”.

“He talks about sci-fi books, which completely got me hooked,” Earlington said. “Just the way he spoke about them, and his humor behind each review, really inspired me to pick up these books.”

Thomas, who started his small booktube channel three years ago, is known for his funny video skits. He says he tries to incorporate his personality into each video, because he wants viewers to be intrigued.

“We live in a time in which I feel people have less patience to just sit around and watch a boring video, or read a boring news article review,” he said. “There is an entertainment element we bring to the table, that it’s meant to bring viewers back visit to our YouTube Channel. My humor and skits definitely have a factor in that.”

Vidcon, an online video conference in Southern California, saw the biggest focus ever on booktube at its 2018 conference, with the most popular booktubers from around the country attending.

Enter the publishers

Book publishers have caught on to the trend, and are now trying to create channels of their own. HarperCollins developed “Book Studio 16,” to cross-promote its own books (it has so far attracted fewer than 1,000 subscribers). Other book publishers, among them Penguin, are following suit. A worrisome prospect: will publishers try to coop booktubers, and pay them to deliver positive reviews? That would hurt booktubing’s current trust environment.

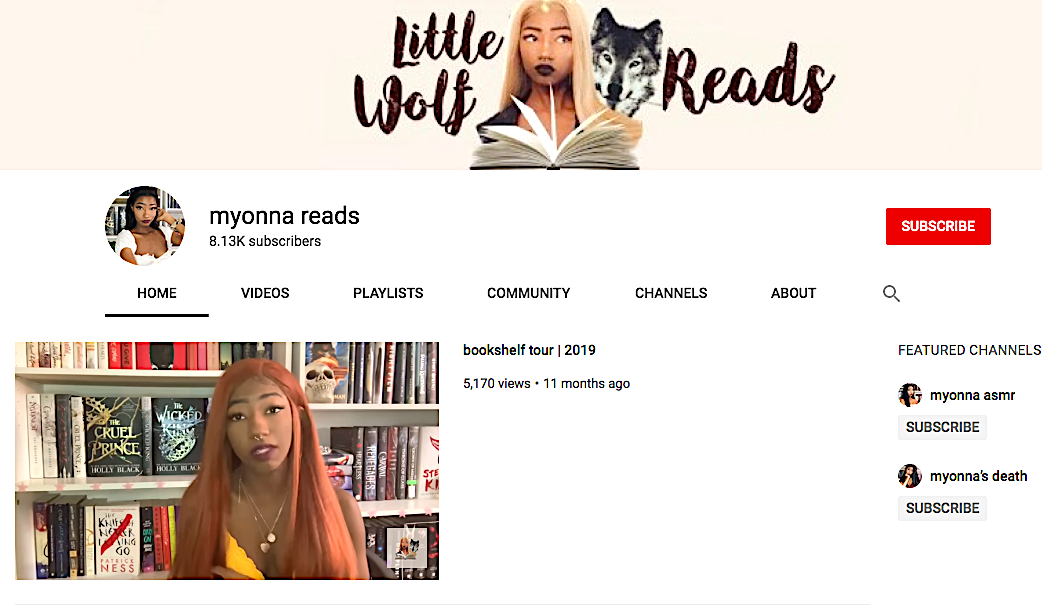

Some African-American booktubers say they feel discriminated against: that white booktubers attract far more attention, and work. Booktuber Myonna Johnson and others started the social media hashtag #supportblackbooktubers, to try to generate more support.

“There’s definitely a lot more work for our white counterparts,” Johnson said. “It’s not necessarily their fault, because they might be oblivious to it, but for sure the white tubers have it easier.”

Johnson’s channel is called “Little Wolf Reads”. She wakes up every morning in her native Detroit to record her book vlog, in hopes of informing those who have never read books about African-American writers. Johnson has 900 subscribers, but says her numbers have not increased since she started the channel in 2016 [since the issue of race and booktubing was publicized in 2019, her subscribership has ballooned past 8,000].

“The truth of the matter is that most of the booktube subscribers are white, in my opinion, so why would they care about African- American literature? They ain’t black,” she said.

Because of this perception, black booktubers have started a campaign on social media with #supportblackbooktubers hashtag, to try to attract more support.

Lori Roselyn, an avid booktube subscriber from Middletown, NJ, says she was not aware of this issue, but that now she’ll make an effort to support black booktubers.

“I feel so bad, honestly,” she said. “I never intended not to subscribe to any black booktubers, but I feel is important for us to learn about all cultures regardless of race.”

YouTube representatives didn’t respond to queries about the perceived dearth of support for black booktubers.

Flash in the pan, or here to stay?

Booktubers bring an entertaining and witty live twist to reviewing that print reviewers may be unable to match. It is through booktubers’ personalities that others are inspired to pick up a book. Is this just a fad — or will it become an enduring new form of reviewing?

It’s an open question. But booktube’s success should not come as a surprise, as the next generation is much more hooked into watching vlogs than to reading articles on the screen or page. According to the Global Web Index, 50 percent of Internet users aged 16-34 say they have watched a vlog within the past month. Though a Pew Research Center survey conducted July 30-Aug. 12, 2018 found that 47% of Americans prefer watching the news to reading or listening to it, the fact that younger people prefer vlogs might foreshadow change.

Booktuber Zarriah Rose, who runs “myreadingisodd ,” believes the booktube trend will only grow.

“This is never going to stop — and readers get tired of reading,” Rose argued. “So why would they sit and read book reviews? Booktube is a break from reading, because [people] are now hearing. Hearing is the new reading. People are much more willing to come to us to let them know if a book is worthwhile to read. It also gives publisher more reach.”

David Shallcross, a veteran English teacher at Payne Tech High School in New Jersey and a book reviewer for many local publications, doesn’t consider booktubing a threat to the traditional written book review. He believes news organizations should try to combine both styles of review. Book reviewers should create their own booktube videos, Shallcross suggested, and attach them to their published pieces.

“It’s time to accept that we now live in a digital era,” Shallcross said. “Every news article you read nowadays has some kind of video attached to it. It just the reality, like it or not. We need to work together to make sure that none of us fail, but yet both succeed.”

Authors such as Alexis Romay, who wrote “La Apetura Cubana” in 2013, does not mind booktube’s popularity. Romay says he sees a financial opportunity and benefit.

“I think it is interesting that readers would rather see and hear a book critique,” he said. “But I see it as an opportunity to sell my book. Their audience is much larger than [that of] book reviewers, I feel. You know, a lot of them have thousands of subscribers. I think is early to say if it has brought more revenue to authors, but I surely think it has the ability to. Booktube might be the greatest thing to happen financially for authors, because it puts their work out there.”