Paseo Cayalá, Guatemala City’s modern commercial replica of a 16th century colonial town, featuring upscale condos, elegant shops, and gourmet restaurants, was counterintuitively one of the ugliest places I’ve ever visited. As we drove through Guatemala City, I looked out the window and saw, in the distance, the tops of hundreds of creamy-white buildings with sparkling windows, and perfectly neat red ceramic tile roofs. It looked like a wealthy gated community, and I thought we’d just pass it by. But, as I reflected on the strangeness of the place against the intense poverty we had seen elsewhere in Guatemala City, I realized that Paseo Cayalá was indeed our destination.

The rich and the poor

Guatemala City’s 22 zonas divide the city into economically differentiated neighborhoods, a phenomenon eerily similar to the city zones of the dystopian series “The Hunger Games.” The differences between zones are stark: Zona 1 is the downtown, working-class commercial district that is slowly gentrifying – an area that increasingly features art exhibitions, concerts, film screenings and festivals along its famous pedestrian street La Sexta Avenida. It has a gritty feel and is unsafe to walk around in at night, due to thieves and drug dealers. There are many zones like this in Guatemala’s capital: relatively safe by day, but unsafe at night. Many more areas are unsafe both day and night.

Zona 5 is one of many zones marked by extreme poverty, and high rates of gang violence. While we did not actually enter these “slum” zones, we saw them from a distance, as we drove – makeshift, tightly-packed shantytowns made from stray pieces of cardboard and tin, old tires and other discarded items.

Our van driver told us that the city had stopped putting flat metal signage on the roads because people so often stole the signs, to serve as makeshift roofs for dwellings. The shantytowns are perched precariously on the sides of steep hills and valleys, creating dangerous living conditions for the millions of people whose homes are vulnerable to being swept away in mudslides. These communities also lack basic services, such as sewer systems, roads and electricity.

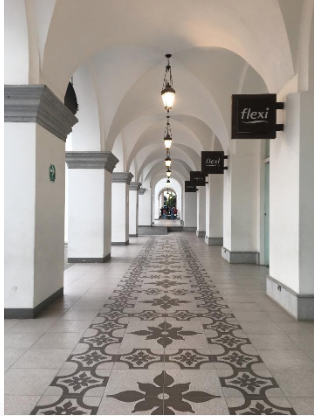

The realities of places like Zona 5, however, only really kicked in when we arrived in Zona 16, the upscale zone for Guatemala’s wealthiest elite, and home to Paseo Cayalá. Like other upscale malls in Guatemala, built to serve the needs of the global elite, armed security guards are positioned at the entry and exit points. People are allowed to enter based on the sole qualification of their physical appearance of affluence. We, as obvious international tourists, were quickly granted entry. But this bothered me even more. As we walked around observing the marble-topped cappuccino bars, avant-garde art galleries where items cost upwards of $1,000 and or steak houses and sushi bars filled with mahogany, white table clothes and romantic candlelight, I found myself hating every finely-trimmed bush, ornately-carved turret and shiny storefront with piped in muzak. What were we doing there?

I battled feelings of confusion, and tried telling myself to take it easy and just enjoy the trip – not out of a wish to ignore the absurdly inhumane contrasts, but as a coping mechanism to get through our evening.

I later learned that many international tourists go to Guatemala City solely to stay in Zona 16, and to live out their Guatemala experience in Paseo Cayalá. Some even claim that Cayalá is the best part of Guatemala altogether, despite never having stepped out of this manufactured world to experience the genuine culture and beauty of other parts of the country.

A mall for the few

Even now, thinking about Cayalá makes me nauseous, and angry, because of the contrasts of extreme wealth and poverty it represents. As we walked around the artificial city, I found myself drawing parallels to similar chic malls that we frequent in the United States. While such malls feel normal in the United States, they stand out in Guatemala, because they are accessible to so few. The fact that I could even be there, having taken planes and cars all the way from New Jersey to one of the most expensive places in Guatemala, forced me to recognize my own privileges as an educated middle-class resident of the United States.

Paseo Cayalá’s developers and supporters claim that, as a privately owned city, it affords all people safety and comfort from the realities of violence in the rest of Guatemala City. But considering that the very cheapest residential space in Cayalá costs 70 times the amount an average Guatemalan makes in a year, it’s clear for whom this security is intended. The wealth gap in Guatemala is so severe, in fact, that about 80 percent of the Indigenous Mayan population lives below the poverty line, living on less than the equivalent of two U.S. dollars a day. That this almost unbelievable difference in quality of life is a daily reality for thousands of Guatemalans is testament to how much Guatemala could be improved if the money in its economy were more justly distributed. Despite being the biggest economy in Central America, with the highest GDP and boasting steady growth rates in the 21st century, large-scale corruption and an unfair tax system allow for wealthy Guatemalans and corporations to pay almost no taxes to support the economic development of the rest of the country. As I stared up at the giant imitation colonial bell tower in the center of Cayalá, I wondered how much better off Guatemala City could be if wealthy business owners invested their money not into manufactured elite paradises, but instead into the infrastructure and development of the real Guatemala City.

How did this level of inequity come to be? It’s owing in large part to centuries-old dynamics of colonization and exploitation of Guatemala’s indigenous majority. More recently, the U.S.-owned United Fruit Company – now known as the Del Monte and Chiquita Banana brands – which maintained control over the Guatemalan economy for much of the 20th century, set the stage for today’s skewed tax system, by entering into deals with various Central American dictators to avoid paying even minimally fair tax rates. Indeed, even when Guatemala gained democratically-elected leaders (from 1944-1954) who dared stand up to United Fruit, the corporation received backing from the U.S. State Department to oust the fledgling progressive political leadership of the country via a US-led coup in 1954 to replace President Jacobo Árbenz with a military dictator who would support United Fruit. Árbenz had won the elections in a landslide during Guatemala’s 10 fleeting years of true democracy, known as the “Ten Years of Spring,” but the coup effectively brought Guatemala back to the same troubling realities of poverty and violence that existed before this hopeful decade.

In the United States, we face similar, though perhaps not as drastic, levels of economic inequality. As of 2013, an average American family of four needed at least $58,000 annually to get by comfortably in their communities, but there are still families of four in the United States trying to survive on less than half that amount. Simultaneously, there are people like Amazon founder Jeff Bezos earning over $8 million dollars in just one hour. As we enter a new Gilded Age of exorbitant wealth for a few and increasing poverty for many more, perhaps we can see how average Guatemalans and average Americans face similar economic forces attempting to cultivate citizens’ complacency in the face of powerful global structures of wealth and control.

As much as I disliked Cayalá, I soon recognized that physically being there was the most eye-opening and memorable experience I could have had to learn about economic inequality. Upon our departure from that almost dreamlike, invented city of privilege, I looked back one last time on its hollow and ugly beauty and thought about how nothing exists in a vacuum – places like that are permitted to exist because of complacency on the part of an elite few.

It may be difficult to convince Guatemalans with privilege to share their wealth. Perhaps those of us from affluent countries could use our fortunately dealt hand to do our part in righting those wrongs. We need to use our privilege to fight against income inequality both in the United States and in countries like Guatemala, with whom we have close historic and economic ties. While individual cultures may differ, many of us face similar struggles and strive for the same freedoms of economic security, health and happiness.