Armed guards and a military truck stand outside Bologna’s only synagogue, itself tucked unobtrusively between two side streets. The discreet tableau is an acknowledgement of the sense of unease local Jewish leaders feel, after years of attacks on sites of Jewish worship across Europe, and today’s global climate of increasing anti-Jewish rhetoric.

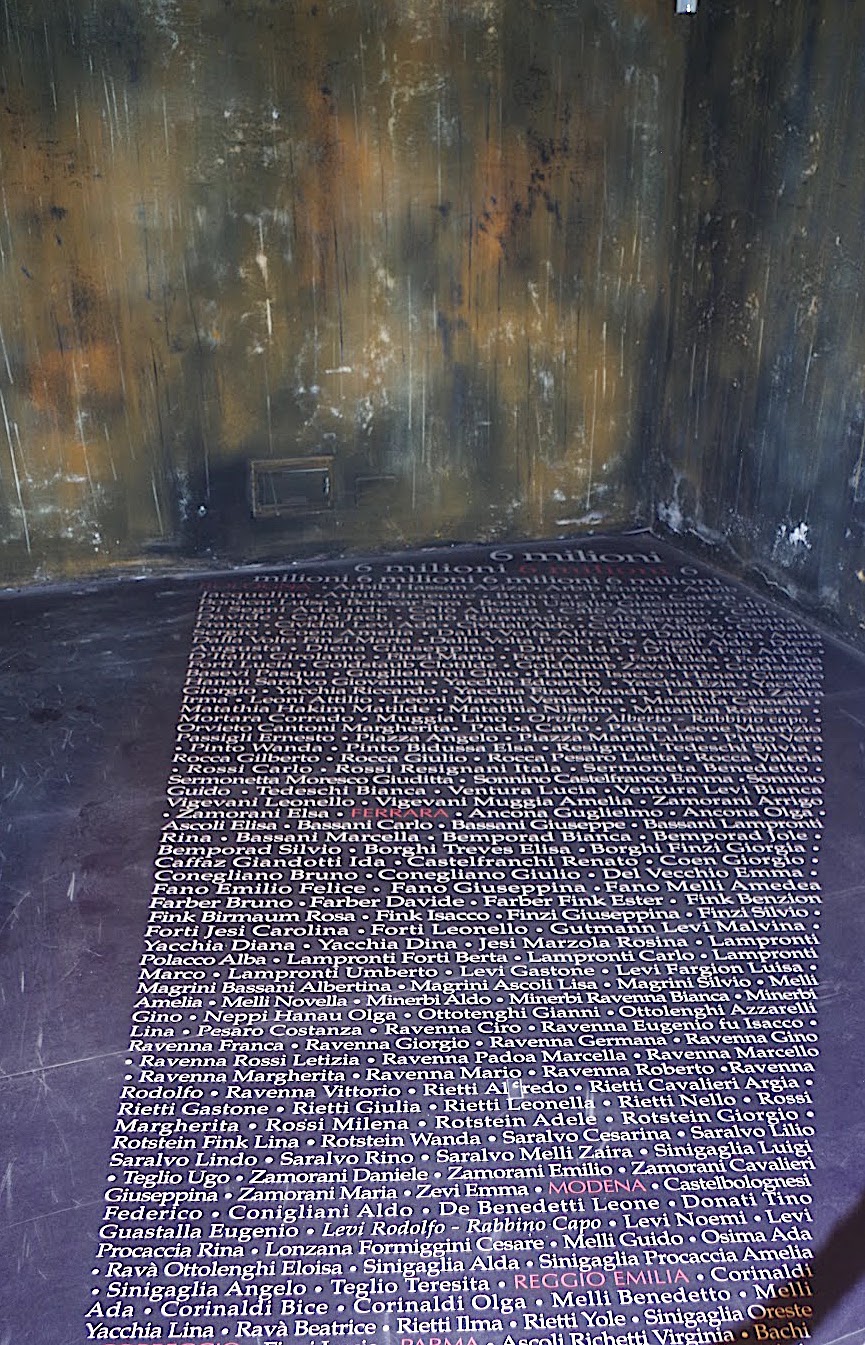

The main entrance is likewise ambiguous, though a memorial slab naming each of Bologna’s Jewish residents who perished in the Holocaust hangs outside.

Outsiders who wish to enter the synagogue must submit extensive documentation, a precaution to discourage potential attacks.

Though this congregation has never been attacked, Ines Miriam Marac, vice president of Bologna’s Jewish community and president of the Jewish Women of Bologna, acknowledges that her biggest challenges are living out her identity, feeling fully welcome within the city’s secular community and keeping her eyes open to the world.

Marac said that she doesn’t feel unduly pressured by the Italian right, or by anti-Semitism, due to the protections the Italian state extends to the Jewish community. But she and others fear these protections won’t last long. And some community members consider shrinking numbers, and lack of cultural preservation, signs of negative change.

Spielberg makes a movie

The close-knit members of Bologna’s Orthodox Jewish community have a good reason to keep a low profile. Their rabbi, Alberto Sermoneta, notes that before World War II, about 300 Jews resided in Bologna. About a third were deported during the war, and never returned (today the Jewish population in Bologna and the surrounding Emilia Romagna region numbers about 500).

Nor will Bologna’s Jews ever forget the affair of the Jewish child Edgardo Mortara, a mid-19th century case that reverberated around Europe, and remains a point of contention today. In the mid-19th century, the boy’s Catholic nanny secretly baptized him, after he fell ill and she feared he’d die. In the eyes of the church, this made the child Catholic – and in 1858, the police appeared at the home of the 6-year-old Mortara, seized him, and put him under the protection of Pope Pius IX, who personally oversaw the boy’s education (he grew up to be a priest).

A wave of panic spread through the Jewish community, and heightened their mistrust of outsiders. The case remains controversial today – mostly because of the split it caused in the Catholic Church, over whether the Pope’s action was just. Stephen Spielberg has announced that he’s making a movie, to be called “The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara”.

But Bologna’s Jewish community finds itself in a relatively peaceful situation today.

Marac recalled that, after the war, Jewish identity grew to be recognized and respected. And, as evidenced by the armed guard outside, Italian Jews receive extensive government and military protection.

Jewish culture is also now celebrated throughout Italy, Marac said. Rome and Milan have large and thriving Jewish communities. Schoolchildren in Bologna visit the synagogue once a year to learn about Judaism. Orthodox religious events are posted on the municipal bulletin boards. There is even an organization, Union of Italian Jewish Communities (UCEI), that officially unifies the Italian and Jewish communities of Bologna.

The synagogue also highlights the importance of women’s roles.

“Jewish women are and always have been important,” Marac said.

The president of the UCEI is female. The Roman president of the Jewish committee is female. The Women’s International Zionist Organization (WIZO) and Association of Jewish Women in Italy (ADEI) fight against anti-Semitism, host inter-faith meetings, and press for the roles and promotion of women. These organizations have female leadership, which is incredibly important to Italians.

Jewish sites in disarray

The synagogue basement features a recent discovery of the ancient ruins of a Roman villa, maintained with help from the Cultural Restoration Department of Bologna. Interestingly, the basement also holds relics from Bologna’s original synagogue, bombed by the Allies in 1943. The old synagogue’s columns are untouched, but visible to those who enter the old temple.

Yet some Jewish sites are in disarray. A combination of general disregard, lack of funds and exposure to the elements have left important places unkempt and forgotten. The buildings in the old Jewish ghetto are covered in graffiti, some of it apparently well intentioned and some disrespectful. Headstones at some of the graves in the Jewish section of the municipal La Certosa cemetery are broken.

Marchelo, a man visiting his late brother’s grave, commented that the Christian plots seemed to be well-maintained; it was only the Jewish area of the cemetery that seemed to lack funds for upkeep. He said he planned to write a letter to Bologna’s Jewish community, to bring awareness to the state of the cemetery where his brother and other deceased community members rest.

The facade of Bologna’s Museo Ebraico is not exempt from vandalism, although the inside is well-maintained. The five-room museum features a detailed narrative of Jewish history in the city of Bologna, beginning with the ancient history of the Jewish people over the course of 4,000 years. Guests can trace this history through an architectural, graphic and multimedia presentation. A separate room is dedicated to Bolognese Jews that fell victim to the Holocaust.

Despite Bologna’s rich and extensive Jewish history, there is no mention of Bolognese Jews in the Bologna History Museum. A curator advises inquisitive guests to “just visit the Jewish museum.”

Nor have all historical sites been recognized and preserved. Bologna’s Piazza Santo Stefano contained multiple buildings dating from the 5th century that were once important Jewish religious centers. Many other establishments were Jewish community staples for business relations at the time. Unfortunately, these buildings have been destroyed, and lack any plaque or commemoration to mark their places.

Palazzo Bocchi is another forgotten historical Jewish building. A Hebrew inscription on the building reads: “Oh Lord, protect me from the lips of the untruthful and from deceitful language.” An additional Latin inscription states: “You shall reign, they say, if you act righteously.” The building has no memorial plaque, and is being renovated into offices and apartments. “For sale” signs advertising office space hang in the windows.

Marac portrays the establishment of the Jewish Museum, now celebrating its 20th year, as a huge victory. It represented the collaboration of a Jewish committee, historians and local government to preserve and appreciate Bologna’s Jewish culture.

The pull of Israel

Some suspect migration to Israel has led to the shrinking of the city’s Jewish community. Although many are attracted to larger Italian cities, most simply want to live in Israel, which Italian Jews consider a melting pot of religious freedom, food, and choice, local religious leaders say.

Making aliyah, a commitment that results in a pilgrimage or immigration to Israel, is very important to Italian Jews, as is serving the two years of military service required of most Israeli citizens. But immigrants to Israel over the age of 25 are not required to serve — a situation some would-be Italian Jewish immigrants find appealing.

Discovery of a 14th century cemetery

A recently discovered Medieval Jewish cemetery was excavated after 2012, after workers attempted to build an apartment complex over what was at first taken for a former nunnery. Archaeologists date the site to as early as the 14th century. It was determined that the cemetery was abandoned and desecrated in 1569, following a decree issued by Pope Pius V that expelled Jews from cities within the Papal states.

Four medieval headstones, and dozens of gold, silver, bronze and jeweled artifacts, had been recovered by 2019, and were being displayed in the city’s Jewish and archaeological museums. The apartment complex was completed after the excavation, with residents now living atop the resting place of some 150 men, women and children.

While many Bolognese Jews consider their community overlooked, they also have hope in the future. Marac says that, while stereotypes are difficult to combat, she and the community hope younger generations will continue to fight anti-Semitism, and maintain their traditions.

About the Author

Mia Boccher and Meghan McCarty

Professor: Mary D’Ambrosio

Class: Global Journalism in Bologna, Italy: International Reporting

Takeaway: