More than 170,000 Ukrainians fleeing the Russian invasion have arrived in Italy, with nearly a quarter settling in Bologna’s Emilia Romagna province. Demographers think some may be joining friends and relatives in Bologna’s already significant Ukrainian community, where many Ukrainian women work as home health care workers for the elderly. Some 7,600 Ukrainians were living in Bologna before the war broke out.

Oxana, 35, left her hometown of Halych with her two children in late February 2022.

“When I was in Ukraine I worked there and had a normal life, but then I lost everything,” she recounted in an interview. “I wanted to come back to Italy as a tourist, not a refugee.”

But Oxana, who asked that her surname not be published, said she was pleased and relieved by the warm reception she’s received.

“I feel welcomed here, and feel like Italians are really trying to help us all,” she said through an interpreter. She and her family were resettled by the religious social service organization Opera Di Padre Marella “This organization helped us find a home … so I feel supported,” Oxana said.

Opera Di Padre Marella also helps connect refugees to doctors, and helps children enroll in local schools.

Arriving Ukrainians have been enthusiastically welcomed by multiple relief organizations. By summer 2022, record numbers of local applications to volunteer had been submitted. The Vesta Project, a 10-year-old refugee resettlement agency, reported receiving 1,000 requests to host or help in a single week. In fact, sometimes there were more would-be hosts than refugees.

But not everyone is happy to see more refugees arriving from the east.

Emilia Romagna region environmental councilor Irene Priolo was among those sounding the alarm over the rising numbers of arriving Ukraine refugees.

“There is great concern about the reception of such a large number of refugees,” she told the magazine Bologna Today. “It will also be necessary to consider the placement of refugees in a more proportional way. If the flow of refugees increases, more funds will also be needed, not only for accommodation facilities but also to allow the reception of refugees.”

The Italian government has authorized three-month, €300 monthly grants to Ukrainian arrivals who find independent accommodation. Ukrainians are also eligible for a special 12-month residence permit that allows them to work, access education and healthcare and claim Italian social security benefits.

Predicaments

Nadia, 31, arrived in Bologna from Kyiv with nothing but a small suitcase to remind her of the life she’d left behind. Her two small children clung to her leg.

Vesta Project case manager Marina Misaghi Nejad talked about Nadia’s predicament.

“Everyone reacts in a different way, and that is because they react to trauma in a different way,” she said. “When they flee from a country, we assume it is from war, and they normally have to flee fast. Usually they are leaving behind husbands, sons and jobs — their normal, usual lives.”

Refugee resettlement workers say that Bologna’s reputation for embracing those needing refuge tends to attract more arrivals.

Sudden flights

Nadia, who asked that her last name not be published, explained how she, her sister, their children and their mother were forced to leave Kyiv so abruptly that they couldn’t retrieve passports.

Many refugees carried no documentation when they crossed into Poland or Italy.

“Technically it is impossible to travel without a passport, but since the war started, the borders have been quite open to welcome Ukrainian refugees in foreign countries,” Nejad explained. “A lot of [refugees] traveled without any kind of document, but foreign borders have been quite open.”

Arriving in Bologna

Women and children make up the majority of arriving refugees, as they have been forced to leave husbands, sons and other male relatives required to stay behind to fight. Not only are these individuals dealing with the trauma of a raging war, but also with the guilt of leaving their partners behind.

Vesta Project members don’t ask refugees about who or what they’ve left behind, Nejad said. They realize that most refugees have left loved ones, and do not want to trigger already-frightened people.

Organization leaders instead focus on offering a warm welcome.

“When Ukrainian refugees come here they are welcomed in a central hub that was organized by the city of Bologna, and by the city protection,” Nejad pointed out.

Settling in

But arriving in Bologna brings no instant relief. Ukrainian refugees have been forced to acclimate to a different country, society and language – on top of the trauma of abruptly losing everything they’d once known.

Refugee organizations aim to provide refugees with a safe place to stay indefinitely. The refugees are given funds to purchase food, and the means to receive medical attention.

“This possibility to be inserted into host families is extended to mothers and children coming from the Ukraine, Nejad said. “We try to give them the best place possible for their needs.”

Refugees being helped by this project are assigned to a case worker, who mediates between Ukrainian families and their hosts.

Ivan, 12, said he is happy in Bologna. He goes to school, and has made friends. His interpreter mentioned that Ivan plays soccer with her younger relatives. He has found some sense of comfort and belonging.

Ivan and Oxana have both attended San Michele dei Leprosetti, a Greek-Catholic church serving Bologna’s Ukrainian community. This church and others like it serve as a means for Ukrainians to find community.

Ukrainian refugees’ biggest challenge is navigating the language barrier, Nejad said.

In limbo

Nejad estimated that 30 percent of Ukrainian refugees she meets plan to stay in Italy, while 70 percent seek to return home.

“It is difficult for them to settle in general,” she said. “Here in Italy, bureaucracy is difficult to deal with, so they really have mixed feelings about all of this. In general they want to stay here with their hosts, for a limited amount of time, because their intention is to return to their countries.”

The Vesta Project also helps refugees return to Ukraine. Nejad told the story of one family’s bittersweet return to Ukraine, where they found their husband and father safe.

“She was crying a lot when we had to say goodbye to each other, it was a very emotional moment,” Nejad said, of the mother she helped. “She wrote to me that she is really happy, her house is still there, and she found a peaceful situation back in Ukraine. I really appreciated the fact that she was writing to me to say that everything was good.”

Other Ukrainians would rather stay in Italy, and Vesta workers have petitioned the Bologna city government to help those refugees find more permanent housing. The greatest influx of Ukrainians entering Italy occurred through March and April 2022; by that summer, the numbers had tapered off.

As of October 2022, there were 170,646 Ukrainian refugees in Italy, with Milan, Rome, Naples and Bologna their main destinations, according to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, and Italian government statistics. The shock of this war is being felt throughout Europe.

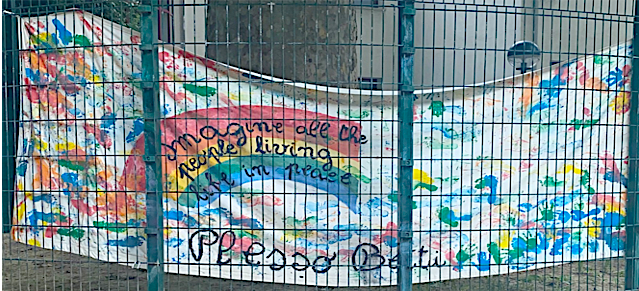

But in Bologna, obvious signs of support for Ukraine and its refugees are everywhere, from anti-war graffiti, to yellow and blue lights shining over the central Piazza Maggiore, to protests and demonstrations, to the rush of refugee aid volunteers.

Said Valentine, a 58-year-old refugee: “Italian people are really kind in general to all of us, and I feel that everyone here is very welcoming and generous.”