A journalist’s investigation attracts death threats, and she’s forced to shut her magazine and flee

Soon after she started university, Lucia Escobar got lucky. She landed her first journalism job writing for El Periodico, a well-known mainstream Guatemalan newspaper. Escobar was invited to be a weekly columnist, providing a youthful (and occasional sassy) take on cultural themes, such as art and movies. She adopted the pen name “Lucha Libre,” (which was also the name of her column). The assignment jump-started her career.

But as she progressed to a better-paid and more prestigious job at a Brazilian news agency, where she was assigned to write about child poverty and malnutrition, her life took an unexpected turn. Though it was the best-paid job she’d ever had, Escobar felt at her lowest. Pregnant with her second child, she wanted to do more than just write about poverty. And life in Guatemala City felt hectic, loud and dissatisfying.

Then everything changed.

Escobar had always dreamed of living a few hours away from the capital, near Lake Atitlán, one of the most beautiful lakes in Central America. A place where billowy clouds seem within arm’s reach, this famous lake is surrounded by blue-green volcanoes, and Mayan villages. Escobar’s husband understood her dissatisfaction. A self-taught reader and writer with little formal education, he nonetheless encouraged his wife to pursue her dream.

“Let’s go to Lake Atitlán and start our own publication!” he suggested.

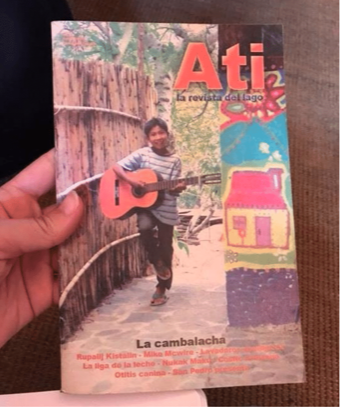

In retrospect, Escobar is grateful for her husband’s initial support. Even with her academic and professional journalism training, she would not have suggested starting a magazine of their own, from scratch. It was a bold idea—as they had no money, and no publication management experience. But with enthusiasm and a shared vision in mind, they made their move, founding a monthly magazine called “Ati,” after Lake Atitlán.

Based in the laid-back town of Panajachel, a stomping ground for artists and international backpackers, Ati focused on four themes: ecology, art, freedom of expression and indigenous rights. The objective was to report in-depth, investigative stories about the Atitlán community, which had no local news coverage at the time. While its authors had originally intended the magazine to be non-controversial, Ati became a vehicle for organized resistance to community problems, such as pollution, tourism-linked overdevelopment and the growing problem of drug trafficking.

Without funds to pay writers, but with strong contacts with local businesses and residents, Escobar and her husband managed to attract some of the top reporters in the country, by leveraging payment in kind. They offered weekend getaways at Panajachel hotels, and restaurant dinners, boat rides and other fun area activities. Funders and locals donated in-kind services to make these outings possible, because they wanted to see Ati continue publishing its great stories.

This system worked for a few years. But eventually it became too expensive to maintain a monthly print edition. As a result, the couple turned the print magazine into “Radio Ati,” and continued to focus on in-depth storytelling.

A terrifying story

But it took just one story, and a bit of naïveté on Escobar’s part, to put the journalist’s life at risk.

In 2013, a series of wild tropical storms wiped out parts of Panajachel. Concerns about community security soon arose, over the pillaging of abandoned homes and businesses. Local men volunteered to start a patrol team that policed the town at night. They covered their faces, supposedly to maintain safety. But an operation that began with voluntary civil defense groups soon turned corrupt. The patrolmen started replicating the abusive practices of the military patrols of the 1980s – the most violent period of Guatemala’s 36-year civil war –and harassing and beating up people they disliked. The town, once a safe space for Escobar’s children to roam freely, now turned dangerous.

Covering the story was dangerous for Escobar, too.

“I didn’t want to write about this topic at first, because it was my community, my family — it’s a very small town,” she recalled. “So, since I had friends [in the capital, Guatemala City] who were journalists, I asked them to cover the issue.”

Though some reporters from the capital did cover the story, not much changed.

Drunk with power, the patrolmen continued to intimidate the townspeople – a dynamic that, one night, led to the murder of a young man. The man’s body was disposed of by the lake, with rocks tied to his feet.

The mother of the youth knocked on Escobar’s door the next day, asking her to expose the story. Escobar knew she could no longer ignore the issue.

She wrote an article exposing the name of the murdered man, and the names of all of the patrol members allegedly involved in the murder. She ended her column by saying: “and if I end up with rocks tied to my feet in a lake, you’ll know who did it.”

In her naïveté, she saw herself as just “the messenger”– not directly linked to the story.

She now knows that she was foolish to believe that covering this story would not put her in serious jeopardy. She began receiving death threats, against herself and her family, something that happens to many Guatemalan journalists brave enough to confront abuses of power.

A 2013 UNESCO Assessment of Journalist’s Safety in Guatemala states: “Since 2000, conservative estimates indicate that at least 19 journalists have been killed in possible connection to their profession; all cases remain unsolved. The lack of conclusive investigation into crimes against journalists is indicative of a chronic, systematic impunity across Guatemala, which has a 98% crime impunity rate nationwide.”

After reading Escobar’s column about the murder, Plaza Publica, an award-winning Guatemalan online investigative news site in Guatemala City, sent journalists to Panajachel to investigate further. As these journalists conducted interviews with the patrolmen, they were surprised to hear them claim that Escobar was a “narco trafficante.”

In retaliation for her story, which resulted in the imprisonment of certain patrolmen, the friends and families of the patrolmen grew angry, and were spreading these rumors. Escobar began receiving texts from drug kings, who filled her phone with messages about “deliveries tomorrow” or with congratulations on supposedly well-executed drug deals. In short, they were planting false evidence, in an effort to discredit her.

Community members began to tell Escobar that she and her family were no longer safe, and should leave Panajachel.

But she didn’t want to believe them.

The discrediting by the patrolmen and their families continued, and soon grew more personal.

Escobar’s husband began to receive texts with messages like: “Don’t you realize that your kids don’t look like you?” These were efforts to imply that Escobar had been unfaithful to him.

Escobar’s family grew increasingly upset with her. Her husband, who had always been supportive, began asking her: “How could you put your kids at risk?!” Her parents were asking the same thing.

“Just for doing my job as a journalist, now I was guilty, and people were angry,” she recalled. The rancor seemed particularly strong because she was a woman.

Soon after these incidents, Escobar packed up her family, left her beloved home in Panajachel and returned to Guatemala City.

Dangers for journalists

Escobar was one of the fortunate ones. Guatemala is one of the most dangerous countries in Latin American for journalists and media workers, who are murdered at alarming rates. In the past five years alone, at least nine Guatemala journalists have been killed, according to statistics from the International Press Institute.

Escobar continues to write her weekly “Lucha Libre” column for El Periodico. The column is now 20 years old. She also writes about social justice issues, as a freelancer for various publications.

Though Ati is defunct, the project provided a critical voice in the Atitlan area for many years, and helped raise awareness of important problems. Escobar’s tale exemplifies what it means to be brave in a country where democracy struggles, and where the denunciation of injustice is routinely suppressed.