The wrenching journeys of Muslims forced to choose between homes they’d know all of their lives, and an unknown land imbued with visions of freedom and independence, have mostly been forgotten.

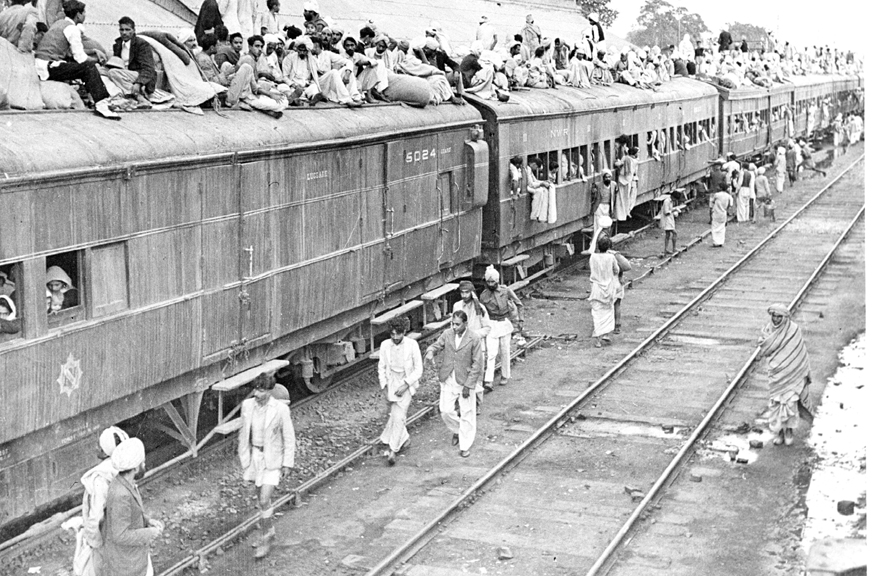

On August 14th, 1947, a line was drawn through India that would result in the birth of Pakistan. But what was meant to be a day of freedom and serenity became one of the bloodiest migrations in history. More than 15 million people were uprooted, and between one and two million people were killed.

After the British left the subcontinent, there was hope for a new Muslim-majority country, one that would allow Muslims to practice their religion and revel in their culture, and to live in peace. The oppression and hate between Hindus and Muslims had only deepened under the British; here, finally, was a chance for everyone to turn the page.

What most people do not remember, though, are the journeys of those who were caught between two worlds, and had to choose between homes they’d know all of their lives, and this new piece of land, imbued with hopes of freedom and independence — yet also questions of uncertainty and fear. If not for the bravery and determination of those who survived that day of separation, there would be no Pakistan. If not for the survivors of the “great divide,” there would have been no freedom.

A Charmed Childhood

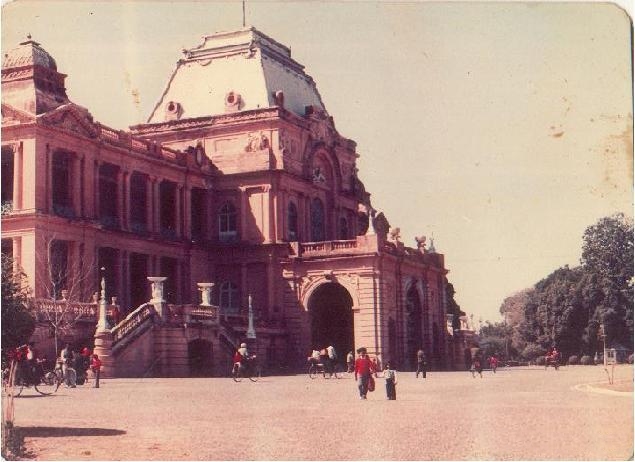

My grandmother, Habib Begum, was born in Kapurthala, India in 1922. She grew up in a large, rambling house, in one of the princely states in the Punjab of British India. Her house was always full of playmates, her own seven siblings, and all manner of cousins. The maharaja (the ruler) of the state was a Sikh, but her own father, a prominent wazir (minister) of the state, was a Muslim. The maharaja’s pink palace was just down the road from their large villa, and marvelous large parties took place all year — a constant source of fascination for Habib Begum and her siblings. They used to watch the resplendent guests, local and foreign, gliding up and down the streets in their novel limousines, at once exotic and modern. She recalled the country she grew up in as totally cosmopolitan and diverse; there were Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Parsis and many others whose affiliations she couldn’t even remember. In her memory, it mattered little, or not at all, what they were. People came from all over India: they were Kashmiris or Punjabis, or from Afghanistan or Iran. There was a smattering of Europeans, too, led by the maharaja’s French wife.

My grandmother recalled her world as one without oppression or discrimination — only unity, love and peace.

Even after she married and moved away, my grandmother would visit Kapurthala as often as she could; she was always trying to relive those enchanted memories of her childhood. On those occasions, she would meet up with her old friends who had made their homes in the old city. These were mainly Hindu and Sikh girls in whose homes she was treated as part of the family. The strong ties she’d made as a little girl never left her, even after she was grown.

But neither she nor anyone else could ignore the reality of the situation. With war raging in faraway places, the thirst in India for freedom from British rule increased. There were riots all over the country, and sit-ins and strikes were rampant. Mass rallies were organized by political leaders of every kind. While Gandhi, Nehru and others were all-India leaders, Mohammad Ali Jinnah was the undisputed leader of the Indian Muslims. My grandmother saw him close up.

Habib Begum and her husband discussed what the future would hold, once the British had left. They all felt that the world would belong to them; that they would live the lives they wanted, as citizens of a free country. Their eyes would glint, and their hearts would brim with excitement, and hope for new freedom.

Then things began to change. Fear began to overshadow hope.

The agitation against the British become more intense, and at times, violent. The rallies grew. Now India’s Muslims were demanding a country of their own. Habib Begum’s father, uncles and husband were caught up in it. Every Muslim, it seemed, wanted to be part of this new world called Pakistan, where there would be no exploitation by the Hindus. The opportunities would be endless, and a true home for Muslims would arise at last.

A Wrenching Separation

At first it seemed that all of the Punjab would be absorbed by Pakistan, and that life for Habib Begum and her family would go on as before — and only get better.

Then on June 3, 1947, it was announced that India and the Punjab would be separated.

Unfortunately, neither my grandmother’s beloved Kapurthala nor her husband’s hometown of Jalandhar would be part of the new country.

Habib Begum was heavily pregnant. Her husband was posted far away and, in view of the difficulties she was experiencing with her pregnancy, she had come to stay with her parents. She’d brought along her beloved little dogs, Duboo and Sonu.

The tales of fighting and bloodshed began circulating, as the Hindus and Sikhs left areas that would soon become Pakistan. It seemed inexplicable that formerly companionable neighbors had become so hostile. People who had lived side by side for centuries suddenly could not stand the sight of each other. Families who had been friends for generations began stabbing one other in the back.

Although her parents were safe, at least for the moment, because of their prominent social position, they were distraught by the daily news of massacred trainloads of people, dead corpses and unsafe roads. Armed bands roamed, killing, it was said, solely on the basis of religious identity.

The maharaja tried to dissuade my grandmother’s family from leaving. But their minds were made up: they did not want to live in a land full of hatred and violence. The place Habib Begum had once called home was beginning to look like a frenzy of hate, terror and destruction. It was no longer the home she knew.

Her husband arranged a large truck to transport their essential belongings. He arrived in the middle of the night on a Friday, at the beginning of August. By then, the situation on the roads had so deteriorated that it was recommended that they only travel in a convoy, with armed protection. There was no time to take many belongings — so my grandmother was forced to leave behind many of her cherished possessions.

Her husband left behind everything he owned. Her parents and her two youngest unmarried sisters accompanied them.

It was heart-wrenching for my great grandparents to leave the magnificent ancestral home where so many of generations of their family had lived, and the place that had housed so many wonderful memories. The officer in charge of the contingent guarding their three-truck convoy asked them to hurry, as they wanted to travel at night: the safest time to move. The truck was filled with their suitcases, and as many family heirlooms as they had been able to gather. Room had to be made for my grandmother to lie down.

They looked for the last time at their house, now a shadow in the dark; and at the limousines. They said goodbye to the staff with hugs, and teary eyes and hugs. Crying, Habib Begum said goodbye to her two beloved dogs, as there was no room for them.

But as the truck began to roll, the dogs stood in front of it, sensing they were being left behind. They began to moan and howl. That proved too much for my grandmother: she had someone scoop them up, and lift them into the truck. They licked her hands, and settled down at her feet for the journey to Pakistan.

Danger on the Road

The roads were full of traffic moving in both directions: of people walking with their all their worldly possessions on their heads, or hauling them in bullock carts or bicycles. My grandmother and her party saw dead bodies on the side of the road, of travelers who had been ambushed and slain.

It was a journey of only about three hours, but it felt to them like an eternity. At least twice, people brandishing long knives, bamboo sticks and guns tried to ambush them, attacking at the windows. Both times, the attackers were beaten back by the armed escort.

Habib Begum felt frightened and sick. But her dogs stood guard by her side. At daybreak the party reached the border, and felt relief. Though they’d arrived safely, they were sickened by the sight of blood, and the dead bodies strewn by the roadside.

It seemed that humanity had taken leave of its senses.

In the new country, they had no choice but to start rebuilding their lives from scratch. They were allotted a house by the government — a shack compared with their former home. There were refugees from the other side, who started looting whatever had been left by the former residents. Social services were non-existent; water and electricity unreliable. But at least this was a land of their own, a piece of the earth where they could once again live in peace.

Eventually my grandmother would settle into her own house, in a small town where her husband was posted. First, though, her son was born, in her parents’ new home on a road called Birdwood in Lahore, on September 22. As she lovingly gazed into her son’s eyes, she felt proud to have given him the gift of freedom. All that she had endured and left behind seemed of no consequence now. One journey had ended, but another had begun.

My Grandmother’s Journey

I never knew my grandmother. She died from a stomach ailment in 1967, at the age of 45, when my father was still quite young. When I asked him to help me write this story, I was expecting a few lines about what life was like back then: about his recollections of his mother’s stories, and maybe an anecdote or two.

Instead, I was able to learn about a chapter of her life I never knew existed. Being schooled for much of my life in Pakistan, I was well aware of the atrocities of war that had happened during the partition. But knowing that a member of my family had experienced it heightened the importance of the odyssey. Through her sons, her country and now through my siblings and I, I realized that my grandmother’s journey had never ended.

My father said that he wanted to tell the story of her life in a way that felt as though she was the one telling me. Writing down this odyssey for you now, I would like to do the same on her behalf – and on behalf of millions of others who took this journey, to build the nation of Pakistan. It took tears, fear, love and strength to finally develop a new country – and peace, resilience and unity. As a citizen of a country so misunderstood by the rest of the world, I know we need to think about these kinds of journeys. We need to think about the stories that held so much change, strength and bravery, because that’s what it took for Pakistan to arise. And now this is my place – the place I call home.