I am typically cast for jobs that require an “ethnic” look, but never for those that call for “gorgeous” “cool” or “the classic American beauty.”

I was born with dark, thick, tight curls. I’ve, since, burned them straight so often that my natural curl pattern has never quite returned. I have dark eyes, an aquiline nose, and an olive complexion – one that gets darker even than a summer’s worth of tanning for others within an hour or two in the sun. I am the darkest in my family. Between highlighting my hair every year since I was nine and banning foundation in any shade darker than “fair,” my mother always told me:

“Don’t tan. You won’t look white.”

My whitewashed elementary school held “immigration day” for the second graders every year. The day was preceded by a month of activities celebrating everyone’s nationalities. Students with parents of different backgrounds were only allowed to pick one. My sister, who is a year older than me, chose to be Italian, representing my father’s side. Against my mother’s wishes, I chose to be Spanish the following year.

I brought gazpacho in as my cultural dish. I begged my mom to sew me a flamenco dress to wear for Immigration Day. I colored a red and yellow Spanish flag, tirelessly working to perfect the off-center coat of arms. I was intrigued by the complicated mish-mash that constituted my mother’s side: her mother, whose parents were from Spain, was actually born and grew up in Puerto Rico. As I crafted my family tree, I found out Grammy was not only Spanish, but French, and spoke both languages fluently – why did my mother speak neither? The thought that I could have been trilingual fascinated me.

“Grammy didn’t teach us Spanish, or anything,” my mom explained when I was in high school, through tears, “because she wanted to assimilate us. Please don’t date him. You’ll ruin what she sacrificed.”

In music class, the teacher – an elder white man – played cultural songs for each nationality in the class as part of immigration month. He told us to stand in front of the class when our respective songs came on.

The seven Italians stood up as he played an Italian song.

The ten Irish clumped together as he played theirs.

The five Russians gathered as he played a Russian song.

The token Spaniard stood alone as he played a Mexican song, face hot. My eyes darted nervously at my snickering peers as the borderline offensive song – which wasn’t mine – blared out.

I somberly told my mom I no longer wanted to wear the flamenco dress.

My childhood memory is filled with small, sad coincidences that never seemed to make sense to me. In spite of my enthusiastic attempts to participate, my music teacher never called on me, instead favoring the blonde girls. I was athletic, but always picked last in gym. I cried when I learned my best friend invited everyone in the class to his house for his birthday except for me. My heart sank every time a teacher told my parents that I deserved recognition for my abilities but never actually gave it to me for reasons that were, frankly, bullshit.

“She deserved to get a 100%. She had the best project by far, but if I gave it to her, she wouldn’t learn.”

“This painting she made is so impressive, it should be in the permanent art collection. She’s just too… young. Next year she will be chosen.”

I wasn’t.

Until immigration day, I never gave much thought to the way my classmates casually insisted I was black or to teachers’ insistent pronunciation of my Italian name, Pinnola, as “Piñola.” They were purely facts of my existence, along with the overarching theme of my life that for some reason, I was never allowed to be the best, even when I was. In my young mind, half of me romanticized myself as an underdog, while the other half prayed to God every night, asking Him what was wrong with me.

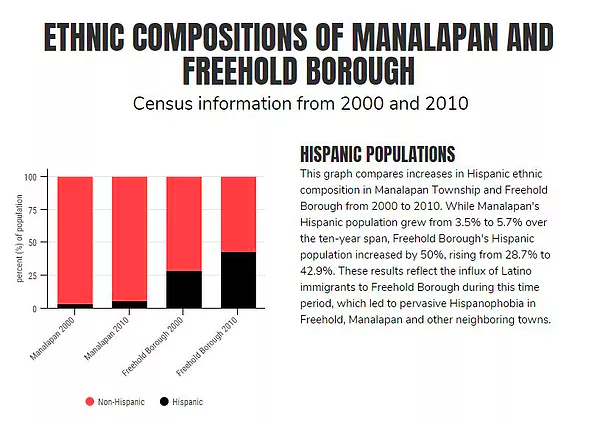

I grew up in Manalapan, New Jersey in the early 2000s. In this time frame, Freehold Borough, a neighboring town located less than five minutes away, had a large influx of Latino immigrants, presumed to be illegal by most. Asbury Park Press reports that, in a little over 20 years, the Borough’s Hispanic population went from 11% in 1990 to comprising half of the town’s population in 2013. The growing immigrant occupation of Freehold Borough led to increasing Hispanophobia in my area. Hispanophobes discriminate against all Spanish people and do not differentiate specific backgrounds within the Spanish scope. In spite of my European ancestry, I was still Spanish, and unique from the other members of my immediate family, my skin made me vulnerable to being singled out.

In third grade, I switched elementary schools. My differences had become more salient to me following the immigration day incident at my former school. Noting the most common questions that came up when other children wanted to be friends – in my experience, mainly: “What are you?” and “Are you Catholic?” – I learned to sway conversations away from my background when meeting my new classmates. I didn’t have to be anything. The Spanish nursery rhymes that Grammy sang while she tickled me were, as far as I was concerned, gibberish, and my Italian cultural connections existed only in my family’s pronunciation of “mozzarella” (MOOTS-ah-rel). The details of my ancestry didn’t matter – unless I mentioned “Spanish,” or worse, so much as breathed the word “Puerto Rican,” – so I discarded them. I was nothing, until my features became even more distinct, and I realized people assumed I was everything.

“Are you Middle Eastern?”

“I thought you were Asian.”

“You have a Jew nose.”

“Definitely Indian.”

“Your ass is Latina.”

“You’re not white.”

“The Struggle of Being Mixed Race” touches on some of the things I’ve experienced.

I attended a vocational high school that was remarkably even whiter and more ignorant than my home school district. Out of my entire grade, there were five “dark people”: two blacks, one Indian, one mixed, and whatever I was. I told the girls I was closest with that I was “mostly Italian” if they asked, which put me in one of the most backward positions I have ever been in. To them, I looked foreign, but since I was technically white, it was okay for my appearance to be the running joke. My casually racist friends pet my curls, jokingly nicknamed me “the terrorist,” “the cleaning lady” and “the slave,” and begged me to wrap things around my head.

Even though I was part of the group, I was simultaneously the outsider, evidenced by the way they all got together without me and arbitrarily excluded me from conversations. I eventually cut these girls off after they made me the scapegoat when they were caught with alcohol – of course, not without the situation “proving” to their mothers that I was the bad influence after all. In retrospect, the glimpse I caught of those girls’ and their parents’ everyday racism was disturbing. However, the differential treatment did not solely come from that group. I couldn’t – and still can’t – wear braided pigtails without being called Pocahontas. Guys flirtily addressed me as Princess Jasmine, and to my discomfort – not to mention the horror of my protective mother – even my high school gym teacher casually mentioned to me and my whole class that “Valerie looks like she would be a successful exotic dancer in Vegas.” People always made commenting on my appearance a priority in some of the most glaringly inappropriate ways I could think of.

I randomly landed a contract with a modeling agency for my dark features, another conundrum in itself. A friend of a friend working as an agency intern explained that they were looking for “racially ambiguous” models and urged me to submit photos. As a favor to the girl, I did, not expecting anything to come of it. Before meeting with me in person or even mentioning their interest in signing me, the agency began submitting those photos to clients without my knowledge. Thus, my ambiguity propelled me towards yet another eye-opening and uncomfortable situation.

I am typically submitted and cast for jobs that require an “ethnic” look, but never for castings that call for “gorgeous,” “cool,” or “the classic American beauty.” As someone who was never fully committed, I don’t think of myself as a model. I have insecurities, like the “Jew nose” my friends loved to point out and my curly hair. As I filter through castings and am able to determine exactly which jobs I will never get, I ask myself if I fit the standard – if I really am beautiful – or if I am a means to filling a small quota in an industry that famously over-represents fair-featured women, noted by journalist Bryce Covert among others. According to Jezebel, which annually counts how many models represent each race in New York Fashion week, while 82% of the models were white in 2013, only 9.1% were Asian, 6% were black, 2% were Hispanic and .3% were “other” races. These stats remain largely unchanged and reflect industry-wide preferences. I ask myself whether I am desirable, or just different, foreign, and weird – therefore necessary to occasionally break the sovereign, bone-white monotony while forever remaining inherently less than the blonde girls.

Among instances of being objectified by peers for their entertainment and commodified for my “ethnic” looks – which are only pretty and have value if a casting director says so – microaggressions dot my memory.

The woman who addressed me as “you people” when I used to cashier for accidentally shorting her a penny assumed I was an idiot because I was something.

My high school counselor told me – immediately after commenting how dark I am – I would fit in well with the multicultural club under the assumption that I was something.

Nearly every time I meet someone new, without fail, I am asked within the first five minutes, “Where are you from?” and the follow-up, “No, what are you?” because I must be something.

My shyness, the way I dance, and my work ethic are among the countless collection of personal traits that people openly attribute to my being something. I smile politely – after all, most people I encounter fully expect me to be flattered by their curiosity – and shrug at the stigmas of the many “somethings” I am mistaken for because I am blessed to be nothing…

Until one of my 8-year-old campers spits at me in disgust, “I heard you were Spanish.”

Until my boyfriend’s mother stops smiling when she asks, and I tell her honestly that my grandmother was born in Puerto Rico.

My mother’s Spanish family was always poor. Neither of her parents could afford to go to college, and nobody would hire her immigrant mother to help support the family. Both of her parents were diagnosed with cancer, becoming part of a statistic. My grandparents are two of the thousands of Hispanic citizens diagnosed with this disease, which, among other chronic illnesses, occurs significantly less among non-Hispanics. According to the Health Affairs policy journal, health disparities among racial and ethnic groups are not biologically determined, but are rather exacerbated by the social and economic stresses of discrimination. My grandpa died at age 50, and although Grammy survived breast cancer, she was later diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s and passed away.

My mom was born with green eyes and light skin and had no accent.

She has been working since she was fourteen. She earned a scholarship at a commutable school and made a career for herself, but she still owed thousands in student loan debt, supported her sick parents and inherited very little when they passed away. According to a study by sociologist Thomas Shapiro, the supplementary, monetary support that her parents were unable to provide or leave for her would have functioned as transformative assets, without which – as is the case for most Americans – continued financial security over generations is not possible. This lack of transformative assets affects racial and ethnic minorities the most, as reported by Pew Research Center. Thus, in spite of her hard work, the cycle of non-accumulating wealth would have begun anew had my mom not married my Italian father, whose parents were non-immigrants, were wealthy enough to cover college tuition for each of their six children and still alive.

My mother’s looks and her non-accented voice set her apart from her own parents. While one of my mom’s sisters had similar circumstances to her own, the other two are single mothers who could not go to college, forced to instead take odd jobs and live paycheck to paycheck. I see radical differences in opportunity, material wealth and quality of life within my own family, differences that carry through to my generation: while I earned nearly a full scholarship for my education, and my family could afford the difference, my cousin doesn’t go to school. My mom’s green eyes and light skin, combined with her natural ability and luck in meeting my dad, allowed her to be the human transition between non-privilege and privilege for her legacy.

Still, my dad taunts her playfully, calling her Puerto Rican and making fun of her dead mother’s voice.

American society is notorious for casually assigning meaning to notions of “race” and treating those people accordingly. According to sociologists Michael Omi and Howard Winant, such meanings are imposed upon people based on their appearance. The visibly white are safe.

On the other hand, those whose physicality fit the criteria of such notions are categorized, discriminated against, and oppressed.

There is, however, a gray area. There are those who can disappear, who have power in passing – in looking white – like my mother, so long as they discard every aspect of their culture.

Then there is me, straightening my hair and staying out of the sun.

Attempting in vain to have conversations that don’t begin and end with my features openly being picked apart, that don’t confirm my fear that how I look takes precedence over my character. I wonder if I ever have a choice – if I have control of who I am – or if that person is arbitrarily determined by someone else every time I am looked at.

In the moments I am left bewildered, an object of hatred, curiosity or perversion beyond my understanding,and in the moments I am reminded that I am Spanish,

He finally answers.

He tells me I am helpless.