With thousands of New Jersey children sickening from lead poisoning every year, some university scientists are zeroing in not only on corroded pipes and industrial dumps, but on a substance called “biosolids,” or “sewage sludge” – a potentially heavy metal-laden fertilizer that could be contaminating soil, and entering the water supply.

Some scientists question the use of sewage sludge in farming, warning that it could contain dangerous lead.

Cornell University soil chemistry professor Murray McBride has been researching toxic chemicals in soil and water for the past two decades. One reason toxic chemicals like lead persist in New Jersey soil today, he said, could be the use of sewage sludge.

“Sewage sludge inevitably has toxins, which at some levels could harm soil, be taken up by crops or potentially poison animals or humans,” he said in an interview.

Joseph Heckman, a Rutgers professor and extension specialist in soil fertility, agreed. Rutgers prohibits sewage sludge fertilizer – often marked on packages as “biosolids,” a word critics call a euphemism – from being used for growing vegetables, he said.

“The New Jersey Agriculture Experiment Station does not recommend sewage sludge for vegetable crops, due to its possible exposure to uptake of heavy metals like lead,” Heckman said.

According to a study by the Cornell Waste Management Institute, EPA rules for the management of biosolids only regulate nine contaminants.

That approach lacks rigor, complained John Leary, general manager of New Brunswick’s George Street Co-op.

“They check for nine different chemicals plus fecal coliform, which is poop bacteria,” Leary said. “Nine to the ubiquitous amount of chemicals being dumped down our drains. If you sold me a Brita filter and told me it only filtered nine chemicals, I’d throw it away.”

Big Fight

The debate over whether sewage sludge is leaching lead into the soil, and from there into the drinking water, is still very controversial among scientists, but may eventually offer some answers about why New Jersey soil is permeated by heavy metals.

“Lead is in sewage sludge,” Heckman said. “There are those who argue that sludge has properties about it that prevent biological availability of heavy metals. But there are questions about whether these properties will be effective for the long term.”

Biological availability is the degree to which a substance is absorbed into a living system.

Heckman said there are many ways to kill pathogens and extract heavy metals, but whether methods such as applying lime to raise acidity or composting are working is not known for sure.

McBride agrees.

“Land application is the easy way out, the cheap way to go in the short term. But is it really the best way to go in the long run?” McBride questioned.

Past lead contamination from leaded gasoline and house paint is also a major contributor to the high lead levels in New Jersey. Removal of this harmful heavy metal has proven difficult, according to various university scientists.

William Hlubik, a Rutgers University professor and agricultural agent for Middlesex County, said lead contamination is very common in soil along highways, and near old buildings in New Jersey.

“High lead in soils can be a problem in areas next to old buildings that have had lead paint flake off in the past or near older highways, where the lead from previously leaded gasoline may have left significant deposits,” he said.

Heckman said that lead deposits mostly come from previously leaded paint and gasoline, old orchards, and possibly sewage sludge fertilizer.

EPA officials contacted declined to comment on whether sewage sludge could contribute to rising levels of heavy metals, such as lead in soil.

But U.S. Department of Agriculture Senior Research Agronomist Rufus Chaney defended the use of sewage sludge, saying that it posed no danger, and should properly be called “biosolids.”

“We don’t use the term sewage sludge any more; we use the term biosolids,” he said. “Sewage sludge is the word you use if you’re trying to speak out against the use of biosolids.”

Lead Still the Top Environmental Hazard

The New Jersey Department of Health identified about 3,500 children and teenagers with elevated levels of lead in their blood in 2015. That figure reflects a steady and dramatic falling trend since 2000, when more than 27,000 children under age 17 were so identified.

Still, lead is considered the state’s top environmental danger to children’s health. Children exposed to lead are at risk for a number of health concerns, and even death — especially if they breathe the lead in, said Elyse Pivnick, director of environmental health for the Trenton-based community development organization Isles Inc.

“At low levels, it can affect children’s ability to learn and control behavior,” she said. “At higher levels it can cause seizures, even death.”

[pullquote align=”full” cite=”” link=”” color=”#fca78a” class=”” size=”25″]”The New Jersey Agriculture Experiment Station does not recommend sewage sludge for vegetable crops, due to its possible exposure to uptake of heavy metals like lead.” – Rutgers University professor and soil fertility specialist Joseph Heckman [/pullquote]

Chaney said the high lead levels found in the blood of New Jersey children was very sad – but he argued that sewage sludge was not to blame.

“It is usually found that when lead levels are above 10 micrograms per deciliter [the EPA blood lead toxic limit], there is a paint source indoors, or there is a parent working with lead and not changing clothes at their workplace, which is required by federal law,” he emphasized.

The EPA standard for lead poisoning is 10 micrograms per deciliter of blood. But the more stringent standard, used by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a “reference level,” is 5 micrograms per deciliter.

EPA statistics show that New Jersey communities whose residents have the highest blood lead levels include old industrial cities, such as Trenton, Newark, Jersey City, Atlantic City and New Brunswick.

In 1994, about 5,000 children in New Jersey were found to have blood lead levels of 20 ug/dL, or double the allowable amount of lead in blood, according to the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection.

“Lead paint was applied to housing and bridges over 100 years ago, used in our factories, used in our water pipes, and used in gasoline,” Pivnick said. “Lead was removed from gasoline and paint in the 1970s, which helped bring national lead poisoning rates down, but the problem remains in our inner cities, where there is a disproportionate number of older housing that is poorly maintained.”

But some scientists suspect lead in sewage sludge could also be a factor.

Heckman said lead cannot be easily removed from soil.

“Once you add heavy metals to the soil, they’re pretty much there permanently, as long as that soil is there,” he said.

Lead contamination can be found in New Jersey water supplies, too, particularly around Superfund sites, such as the Raritan Bay Slag Superfund.

The New Jersey DEP found high levels of lead along the southern shoreline of the Raritan Bay, near the Old Bridge Waterfront Park, according to a 2007 EPA report. Warning signs were posted around the park.

Seven years later, in 2014, the EPA finally conducted a $79 million cleanup of the Raritan Bay Slag Superfund site, where lead waste existed historically, from a seawall and jetty near the beach.

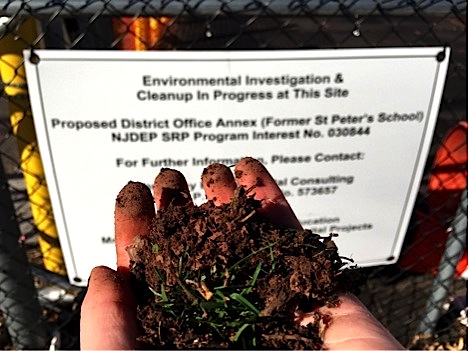

There are about 150 Superfund sites in New Jersey. Tim Larigan, an environmental scientist at Brinkerhoff Environmental Services, Inc., said he conducted an environmental assessment of a Superfund site in central New Jersey in fall 2015 that likely had dangerous lead emissions.

“The site was a former hazardous waste management facility that treated and recycled waste,” Larigan said. “The facility also stored large quantities of contaminated soils containing various heavy metals, including lead, on site. Based on the information gathered, it is likely that dangerous lead emissions took place there.”

In terms of heavy metal cleanup, the main concern among university researchers seems to be the long-term implications of lead contamination in Superfund sites.

An Old Problem

Lead contamination is not, however, a new issue in places like New Jersey or Flint, Michigan, which recently faced lead pipe water source contamination.

[pullquote align=”center” cite=”” link=”” color=”#fca78a” class=”” size=”25″]“If you sold me a Brita filter and told me it only filtered nine chemicals, I’d throw it away.” – George Street Coop manager John Leary, complaining that EPA standards applied to fertilizer are too loose.[/pullquote]”

The Flint case is a classic example, but that is not new,” McBride said. “That happened in the city of Washington 10 or 15 years ago. Almost the same thing happened there, and people have forgotten about it.”

In 2004, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found lead contamination in Washington, DC drinking water, at 83 times the accepted limit.

In terms of safety, there are ways to get soil and water tested to keep lead exposure to a minimum.

“It is wise to conduct a soil test and ask for a special lead test if you suspect that lead may be a problem,” Hlubik said. Residents can pick up soil testing kits from their local County Cooperative Extension office, he said.

It’s not enough to simply test the soil, though — government regulations should constantly be questioned to ensure water and soil protection policies are up to date, university scientists say.

McBride said young people should take a look at what he considers relaxed governmental regulation of toxic materials in soil and water with regard to lead and other harmful chemicals.

“Young people should be asking government officials hard questions ,like ‘Why are you always choosing the short term, easy way out?’ he suggested.

How to Stay Healthy

Families with young children should take steps to minimize lead exposure, according to Heckman.

“So far as I know, there’s no biological value to lead, so the lower the exposure the better,” he said. “Consider ways to prevent exposure, such as not tracking dirt indoors where kids can ingest it later, and steering clear of growing leafy green vegetables like spinach that grow close to the ground, because soil splash could contaminate them.”

Heckman said heavy metals like lead in New Jersey soil and water may be here for a long time, due to high cleanup costs.

Chaney said environmental cleanup projects progress slowly, due to high costs.

“The time to conduct an environmental remediation operation depends on the size of the problem and the rate of funding,” he said. “Many are slowly funded, or the initial funding is consumed when they find more important contamination at a site.”

This story was awarded second prize in the 2016 New Jersey Student Environmental Reporting Contest, part of the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation-funded collaborative reporting project Dirty Little Secrets: New Jersey’s Toxic Legacy.